Procedure Guide

Persistent, high volume (>1000 mL/d) chylothorax or low volume chylothorax that has failed 1-2 weeks of conservative management

Traumatic chylothorax (80%): thoracic surgeries, blunt/penetrating trauma

Non-traumatic chylothorax (20%): idiopathic, lymphoma > SLE, Behcet's, TB, congenital anomalies (e.g. Gorham’s dx, lymphangiomatosis), plastic bronchitis

Chylothorax risks: hypovolemia, malnutrition, and infection

Other chylous syndromes, e.g., chylous ascites, chyluria, lymphatic leaks

Obstruction and Collateral Flow, e.g., lymphocele

No safe access

Active right to left shunt for oil-based contrast

INR >1.7, Plts <50K, or uncorrected coagulopathy

Conservative management (low-fat diet or TPN and octreotide) often not successful but tried first (~28% efficacy).

Embolization: generally 70-80% efficacious without complications.

Modified with used of SCDs on calves can decrease procedure time with >90% effecacy.

Failures are often secondary to congenital lack of cisterna chyli or comparable target for canalization.

Surgical thoracic duct ligation is highly successful but has 35% morbidity and 2.1% mortality.

Obtain labs (PT/INR, CBC, CMP, GFR)

Consider dynamic contrast enhanced MR lymphangiography (DCMRL) to characterize anatomy.

This is particularly important for chylous ascites. If you go straight to thoracic duct embolization, you will likely make it worse. Instead, this may require decompression of the lymphovenous junction from debris or addressing an intra-abdominal leak.

Could also get a CT to exclude portal vein thrombus as a cause of chylous ascites.

Hold antiplatelet agents 5d pre-op if possible.

Some give prophylactic antibiotics.

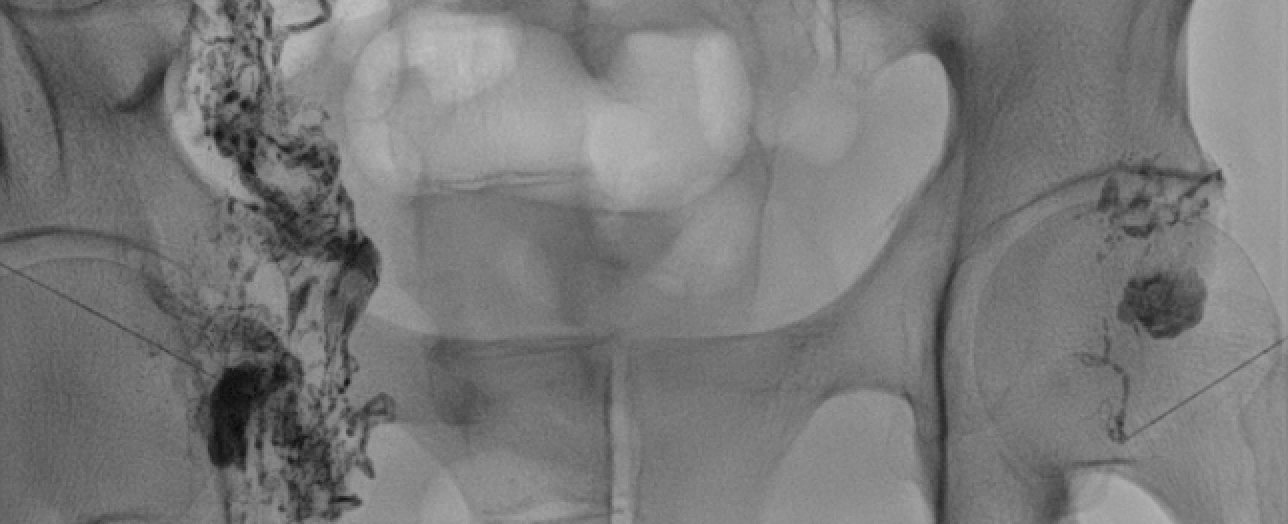

Perform diagnostic lymphangiogram to ideally opacify the cisterna chyli for access and identify leak

Nodal approach is preferred due to efficiency

Access hila of bilateral inguinal lymph nodes with a 25G spinal needle attached to K50 tubing with lipidol syringe via a long lateral subcutaneous course for stability

Test injection of lipiodol to confirm access

Some will use Dermabond to further secure needle positioning

Slowly inject lipidol at 0.1-0.2 mL/min intermittently checking progress with fluoro (often takes a LONG time). Max dose of 6-8 mL unilateral, 12-16 mL bilateral.

Placing SCDs prior to the procedure can help make it more efficient.

Alternative is traditional pedal access

Inject methylene blue between toes just beneath the epidermis to identify lymphatic vessels on the dorsal aspect of the foot

Make an incision and carefully exposure the lymphatic vessel

Cannulate vessel with a 25G or smaller butterfly needle

Slowly inject lipidol as above

Percutaneously access the cisterna chyli or prominent retroperitoneal lymphatic duct with a 15 or 20 cm 22G chiba or 21G trochar needle under fluoroscopic guidance.

Classic teaching was to try to avoid traversing colon but later studies suggests it doesn’t matter.

Advance 0.018” wire (e.g. V-18) into the thoracic duct followed by a 2.4 Fr microcatheter over the wire

If unsuccessful, an alternative is thoracic duct disruption with the needle

Inject contrast to confirm positioning and perform diagnostic angiogram.

Alternative access techniques

Transvenous retrograde - can obtain left cephalic or basilic access and try to access whether the thoracic duct traditionally drains into the confluence of the left IJ and subclavian, 4F or 5F RIM is a good catheter for this but challenging to select and lots of variable anatomy.

Direct retrograde - sometimes the termination of the thoracic duct can be visualized with ultrasound and directly accessed with a micropuncture set.

Interventions

Leaks/chylothorax -> embolization.

For chylothorax, sometimes selective embolization can be performed. Otherwise, you can embolize that thoracic duct. Best done with coils as a back stop and glue. If can’t access the thoracic duct, maceration by spearing it with the access needle multiple times can be effective.

For chylous ascites, this may require access of the most adjacent lymph node or even the hepatic lymphatics followed by intranodal glue embolization.

For lymphoceles, the approach is similar to above for chylous ascites with intranodal glue embolization of the most adjacent node. Alternatively, the ducts leading to the node can be accesses and embolized, though this is VERY technically challenging. Other alternative is to puncture close to the afferent lymphatic and inject 1-2 mL ethanol to effectively ablate it.

Chylous ascites without leak, protein losing enteropathy, abdominal pain

Sometimes this is caused by obstruction of the lymphovenous junction by debris/clot. It can also be causes by adjacent venous stenosis in the setting of pacemakers and other cardiac devices.

This can benefit from decompression, using a 5 mm balloon to open up the junction. Stents have been tried but do not tend to work.

Diarrhea and LE swelling > infection, bleeding, injury to the aorta, IVC, intestine, or liver

Daily chest radiograph with chest tube in place until output <200 mL/d.